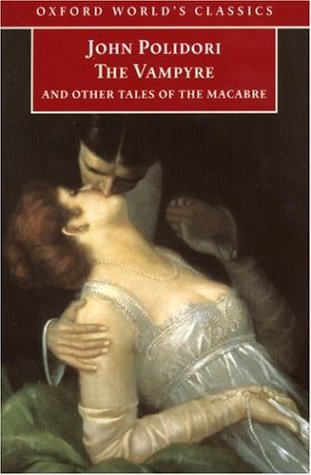

Over the past few days I was on vacation and read John Polidori's The Vampyre alongside Lord Byron's Augustus Darvell (AKA "A Fragment"), which are both reprinted in a recent Oxford collection. This turned out to be a fascinating little assignment for any vampire fan.

The importance of Polidori's Vampyre has been documented well enough; the story, first published in 1819, was an outgrowth of the 1816 Villa Diodati party at which Byron, inspired by the German horror anthology Fantasmagoriana, challenged his guests to each write a scary story.

Technically only two complete tales resulted from the challenge: Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, published in 1818, and Polidori's 1819 Vampyre. Polidori's story was the first modern vampire tale, taking the folkloric concept of the ghoulish, decrepit peasant wraith and transforming the vampire into a satire of upper-class devilishness. The villain, Lord Ruthven, is a thinly veiled parody of Lord Byron, Polidori's former employer and friend. But when Vampyre first appeared, it was credited to Byron, a fact that appalled both Byron and the actual author.

Polidori felt robbed of his due credit and Byron-- the single most famous author in England at the time-- felt besmirched, not by the portrait of him in the story, but by any writing he didn't perform. Further, Byron hinted at plagiarism: apparently Byron had told a story at the party that had come out very similarly to Polidori's Vampyre. This idea-- that Polidori had in fact stolen the story-- moved Polidori to write in a note in his 1819 novel Ernestus Berchtold that in fact Vampyre was suggested by a kernel of an idea from Byron:

The tale which lately appeared, and to which his lordship's name was wrongfully attached, was founded upon the ground- work upon which this fragment was to have been continued. Two friends were to travel from England into Greece; while there, one of them should die, but before his death, should obtain from his friend an oath of secrecy with regard to his decease. Some short time after, the remaining traveller, returning to his native country, should be startled at perceiving his former companion moving about in society, and should be horrified at finding that he made love to his former friend's sister. Upon this foundation I built the Vampyre, at the request of a lady, who denied the possibility of such ground- work forming the outline of a tale which should bear the slightest appearance of probability. In the course of three mornings I produced that tale, and left it with her.

Byron, meanwhile, insisted that his publisher release The Fragment that appeared at the end of Mazeppa. That story, though unfinished, hews closely to Byron's kernel.

Here is what I can report on reading them both together:

They are very different stories. Though Polidori clearly took Byron's idea as inspiration, the Polidori story is essentially a satire of Byron overall, and has a wry, cynical, almost modern voice.

[Aubrey] hinted to his guardians, that it was time for him to perform the tour, which for many generations has been thought necessary to enable the young to take some rapid steps in the career of vice towards putting themselves upon an equality with the aged, and not allowing them to appear as if fallen from the skies, whenever scandalous intrigues are mentioned as the subjects of pleasantry or of praise, according to the degree of skill shewn in carrying them on.

His description of Ruthven/Byron is withering: Ruthven is handsome, rakish, and demonically cruel, giving drink to drunks and money to gamblers, but hastening the destitution of the desperate and despoiling the pure. He is capable of great kindness, and nurses Aubrey back to health, before turning cruel again. And it turns out he's a literal vampire. The dramatic moment of the character's death in Greece-- shot by bandits in an action scene-- is only used to set up the vampire's return.

Byron's tale is not a complete story, but in general it is clearly a poetic work of heavy symbolism and high language. The central focus is still two men, one a Byronic character-- rich, dangerous-- but where Polidori's version is only begrudgingly sympathetic, Byron's is rather self-impressed:

I heard much both of his past and present life; and, although in these accounts there were many and irreconcilable contradictions, I could still gather from the whole that he was a being of no common order, and one who, whatever pains he might take to avoid remark, would still be remarkable.

The death of the remarkable Augutus is more like a piece of folklore-- he makes the trip to Greece specifically in order to die and begin a year-long rebirth, and he presses the narrator to complete this revival by throwing a ring into a river.

So: Byron's is a lovely enough-- but abandoned-- story; prose never held his interest. Polidori's story is funny if melodramatic, and very modern, especially in that it gave us the modern, Byronic vampire. One thing's for sure: without Polidori and Byron we would have no Byronic (wan, sad, sexy) vampire at all, no Dracula, no Carmilla.

Would love to hear anyone's comments!

John Polidori is THE best and forever will he be immortal just like his vampyre and I love him. ~x~

ReplyDeleteJolene, do you have any info on Polidori's friend, Madame Brelaz, who apparently had a hand in publishing The Vampyre?

ReplyDeleteGlad you liked the post! Polidori actually plays an important role in the book I have coming in May.

Thanks for your note about Naschy-- I had been kind of caught up and ignoring news, so I missed that. I'm really excited that you mention he did a version of the Vampyre! I wonder where I can get that.

ReplyDeleteIt is strange that the Ruthven story, which was incredibly popular in its day-- just last night I read a long diary entry from Dumas on seeing just one of many play versions of Polidori's story-- hasn't had the same success onscreen. It might be a little short on action, but I'd expect half a dozen barely recognizable adaptations. I guess the main reason is really, no one remembers The Vampyre. If they did, we'd have more of them, because a recognizable brand makes a difference.

But I agree completely-- plagiarism has nothing to do with The Vampyre. The most I'd say is it's "inspired" by Byron, his work and his personality.

Jason - The Vampyre is an extra on the Diemos release of Human Beasts.

ReplyDeleteTaliesin, I will check that out!

ReplyDelete